Unique stories

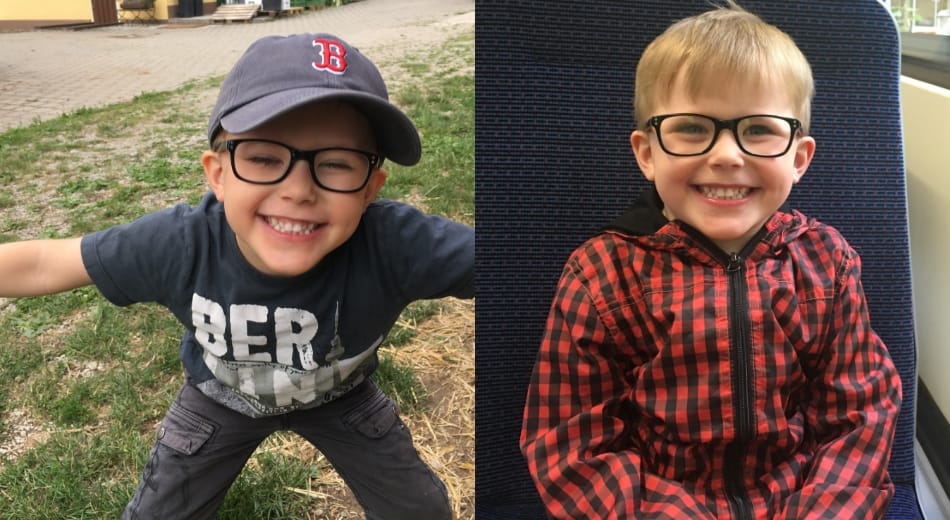

“I don’t want to lose this smile” – a mother on her son’s RB disease

“Pick him up. And come here.”

The ophthalmologist’s words on the phone are unmistakable.

So she picks up her son at the daycare center.

Takes him to the ophthalmologist’s practice.

On her advice, she immediately takes him to Erlangen University Hospital – and only an hour later learns what no mother in the world ever wants to hear: “Your son has cancer.”

An hour ago, he was still playing outside in the nursery.

How can he have cancer now?

Retinoblastoma!

She’s never heard of it.

It’s August 1, 2017.

Carolin will never forget that date.

It is the day that changes her life – and especially that of her son Henry.

Hard times lie ahead for the family.

Uncertain times.

With lots of questions.

And even more fears.

Parents whose children have cancer understand and feel what Carolin feels.

Everyone else can be sympathetic, listen and help.

They are not on an equal footing.

Carolin will also experience this in the coming months.

SOMETHING Hilarious, SOMETHING BRIGHT IN HENRY’S EYE

KAKS wants to find out more about Carolin, Henry and the family.

How did Henry’s diagnosis come about?

What were the signs?

Who discovered them?

We arrange to have a long, confidential conversation.

Which we write down.

For Carolin.

For Henry.

And for so many families whose children had “that damn cancer”.

Or have.

This story is for them too.

It should give them hope and the confidence that life after cancer and cancer treatment is possible.

Just a normal life.

Although there will always be life before and life after.

So many parents of affected children make this division.

Because the incision is there, digging deep into the souls of mothers and fathers.

Sometimes it torments, sometimes it doesn’t.

But it is always there.

Even for Carolin.

That becomes clear in our conversation with her.

She says so herself.

Carolin is a likeable woman.

With a beautiful, warm voice, without a Franconian accent.

She is 42 years old.

An employee of a German airline.

Married to Dirk, a professional musician.

The couple live in Nuremberg and have two sons.

Henry, now four, and Nick, seven.

“Almost exactly a year ago,” Carolin says right at the beginning of the conversation, she saw something funny in Henry’s eye.

She remembers a post on Facebook about abnormalities in the child’s eye.

At first, it remained a faint memory.

But when she sees “something bright” in her youngest son’s eye again barely a week later, she grabs her smartphone, takes a photo of Henry and sends it to her ophthalmologist friend.

She gets in touch immediately: “Pick him up and come here.”

It doesn’t take long before Carolin and Henry are sitting in her friend’s practice.

And it quickly becomes clear that there is no time to lose.

Henry is blind in his right eye.

The retina of his eye is detached.

Blind?

Detachment of the retina?

Carolin’s head is buzzing with thoughts.

What does it all mean?

It’s only six months since she was at this very practice with Henry.

A routine examination.

There were no abnormalities.

Henry just gets his glasses here.

And now this.

The doctors later tell the parents that this rapid development and change in a child’s eye is entirely possible.

The parents go to the university hospital in Erlangen.

The doctors here don’t need an hour to tell Carolin and Dirk the following: Henry has a retinoblastoma.

A unilateral one. His right eye cannot be saved.

Please don’t get your hopes up.

We are no longer operating.

You have to take the child to the University Hospital Essen in North Rhine-Westphalia.

I WANTED TO GET THE TUMOR OUT OF MY CHILD

Sentences like blows.

But there is no time to feel them as hellish pain or as a terrible powerlessness.

In the course of the conversation, Carolin will tell us about the problems that arose after Henry’s recovery.

Very openly.

But she says of those first hours, days and weeks: “I worked well during the peak phase.”

So Carolin and Dirk drive to Essen with the child, who is still a happy boy.

The doctors confirm the diagnosis.

They undergo various examinations, including an MRI.

And set the date for the operation for a week later.

Carolin no longer knows how she got through the week at home until the operation

.

Just this much: “It was terrible. I just wanted to get this tumor out of my child.”

Henry laughs a lot this week as his parents wait for the appointment.

And he laughs, as they say, all over his face.

He knows that he is ill and that the doctors will help him.

Nothing more.

So no reason not to laugh.

For the little man.

For his mother, this carefree attitude is everything: “I didn’t want to lose that laugh. I felt that my child’s life was at stake.”

That’s why everything had to happen quickly.

Quickly.

Quickly.

She really does repeat the word several times.

On Friday, August 11, 2017, the doctors in Essen removed Henry’s right eye in an operation lasting several hours.

And with it the tumor.

The cancer that his mother wanted “out of her child”.

Henry receives neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy after the operation.

Just two days later, on Sunday, the family travels back home.

Follow-up care takes place at different intervals; after six weeks, after three months, after five months.

Sisters Carolin and Dirk show Henry how to apply cream to his eye socket in Essen.

“I can’t do that,” the mother complains at first.

Perhaps out of fear of hurting her child.

Perhaps out of shyness.

Perhaps out of excessive demands.

“But you can,” is the short answer.

The family is not given any more advice.

PANIC FEAR FOR THE CHILDREN

Learning by doing!

That’s the school.

And that’s the big challenge in the first few weeks after the operation.

The so-called cup falls out of the three-year-old’s eye socket several times.

Putting it back in is anything but trivial, at least the first time.

Henry’s ophthalmologist Carolin gives instructions over the phone.

The parents are not allowed to remove or insert the prosthetic eye for the first few weeks.

Only the ophthalmologist is allowed to do this.

This is Henry’s wish.

“Of course we tried to bribe him,” smiles Carolin.

Even the details come back to mind these days.

“Now that it’s the anniversary, it’s all coming back,” says Carolin quietly.

Like the same agonizing questions: Should I have noticed?

Why didn’t I notice it?

“There was a phase when Henry started to hate me.”

A mother has to understand that first.

To come to terms with it.

And resolve it.

Carolin finds help online and makes contact with a mother whose son is Henry’s age.

Amir had lost his eye to cancer two years earlier.

Little Henry recognizes in the boy that he is not the only one “who has something like that”.

That seems to do him good.

The aggression towards his mother stops.

Of course, Carolin and Dirk want to bring up their sons and especially Henry “normally”.

“Sometimes I have to scold him,” says Carolin, “but I find it difficult.”

Henry’s brother Nick and the two cousins respond to Henry with great naturalness and Nick in particular with a lot of love.

But even a seven-year-old reaches his limits – and has thoughts that would never occur to an adult.

“Henry has something special. And I don’t,” he once complains to Carolin.

We tell Carolin about the workshops especially for siblings that the Children’s Eye Cancer Foundation now offers at its RB meetings.

And that many children and young people are taking part.

Who knows, maybe Nick will be sitting in one of these workshops at the next meeting, together with many other siblings who feel the same way as he does.

Carolin is certainly not doing well months after Henry’s operation.

She suddenly develops an anxiety disorder.

We like how openly and reflectively she talks about it: “The deep hole came. I was suddenly terrified for my children.”

She goes to a day clinic.

Eight weeks.

Starts behavioral therapy.

And comes back stronger.

To the family.

To her job at Nuremberg airport.

Dirk has her back during the therapy.

Her sister is also a great support. Even friends of the couple, although there is also an attitude among some that the child’s operation is “over now” and “everything is fine again”.

It is also a relief for Carolin that she finds her way to the Children’s Eye Cancer Foundation.

There are answers here.

Like-minded people.

Understanders.

Encouragers.

We laugh a lot when she tells us how she got in touch with the foundation: “My brother-in-law’s friend has a girlfriend and she is the sister of a friend ….”

The contact is now there and that is good.

Henry goes back to his nursery shortly after the operation.

“The teachers there are great,” says Carolin.

They couldn’t wish for better ones.

They both visit an institute for the blind and visually impaired in the city and get all the information they need.

For Henry.

According to Carolin, he is a completely normal, bright boy.

Even at nursery.

However, Carolin can also see that her younger son is anxious about new things.

“He gets scared very quickly,” she says.

He doesn’t like gymnastics and only plays soccer at home.

THE FEAR OF THE BAD WORD CANCER

Sylt – comes at just the right time.

“Not too early, not too late,” says Carolin.

“Sylt was great.”

The family went to the North Sea for rehab in April this year.

It’s good for all four of them.

It goes deep.

At least for Carolin.

Here she learns to put aside her fear “of the bad word cancer”.

She only says the word during our hour-long conversation.

She is probably not aware of it.

Before Carolin and Dirk go to Sylt, they have to tell their boys the whole truth.

Because so far, Nick and Henry only know that Henry was ill and had to have an operation in Essen.

Cancer – they haven’t told the children that.

But now they have to.

Nick is terrified.

He knows that his grandmother died of cancer.

Does Henry have to die now too?

Carolin and Dirk are able to allay the boys’ fears, which have been with them for months.

Not everyone dies of cancer.

They hold on to that.

So Sylt can come.

And the time in the clinic, by the sea – it will be a success.

Perhaps the word is strange in this context.

But we listen to Carolin rave about the families they meet.

About the friendships they make.

About the good conversations they have with other parents of children with cancer – some of them still undergoing treatment.

Of the outings.

And of the women’s and men’s evenings, which are so wonderfully free of illness and fear.

And of her husband’s guitar playing on the beach on Sylt.

Dirk, says Carolin, has not yet processed the terrible time in his music.

As you might imagine a professional musician would.

But her husband has had good, personal men’s talks with the other fathers on Sylt.

She knows that.

“It was also something special for the men.”

Everyone in the family still draws on this experience.

Dirk, Carolin, Nick and Henry.

The parents have the next RB meeting in Düsseldorf as a fixed date in their calendar.

They are looking forward to the meeting, the encounter with the other families and the encouragers from our foundation.

“It doesn’t always have to mean the worst,” says Carolin.

Looking back on the past twelve months.

And to that day when the ophthalmologist tells her: “Pick him up. And come here.”

The sentence is set in stone.

And it triggers an experience that terrifies the family.

But it also makes them stronger.

Carolin and Dirk’s relationship has become closer.

They both know that this year is part of our lives.

And even if they never imagined it, it’s good the way it is today.

And when they hear from Essen that Henry’s illness is not genetic, it takes a load off their minds.

The interview was conducted by Sabine Kuenzel for KAKS.